Recently, my family and I took a day trip to Walden Pond and the town of Concord, Massachusetts. I snapped a few photographs of the autumnal landscape and the New England townscape and sent them to some friends and relatives. I received this email response from one of my cousins who happens to be a high school English teacher.

"I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived."

No commentary. No personal reflection. Just the words of Henry David Thoreau. I should also mention that I telephoned an aunt of mine that same morning (she, too, a high school English teacher) to tell her of my impending trip, and she literally cried; she wanted to be there so badly. “Oh, you have to tell me all about it,” she insisted. “You have to take pictures! You have to remember to visit Nathaniel and Ralph and the rest of them for me!”

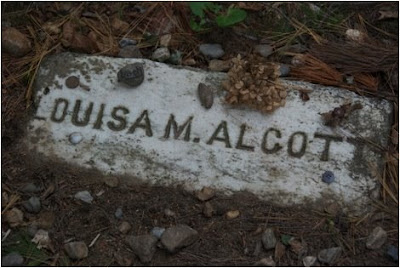

And so we entered the frenzied clutter of cars and pedestrians and cyclists that is Concord’s Main Street on a perfect weekend in October, plopped the two-year-old in the stroller, and started for Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. It seemed that all signs pointed to our destination—Authors Ridge. After maneuvering toddler and stroller over cracks and roots and rocks and cobble, we reached the summit and paused in front of the modest stone markers placed over the remains of great writers made into myths. Several people had already paid their respects by leaving various mementos of their journey to what Louisa May Alcott once pseudonymously called “this modern Mecca” (she used her nickname Tribulation Periwinkle).

Little did Alcott know—or perhaps she knew quite well—that she would be visited by similar sorts of pilgrim-tourists who flocked to Concord in the 1860s and who, in the words of Alcott, “roost upon Concordian fences, chirp on Concordian doorsteps, and hop over Concordian fields and hills, scratching vigorously, as if hoping to unearth a new specimen from what is popularly believed to be the hot-bed of genius.” I wonder how much today’s roosting, chirping, hopping, scratching, and hoping resemble that of the nineteenth century. I wonder how much the myth has changed since the The Scarlet Letter (1850) became THE book to study for the English AP test. I wonder when high school English teachers started crying over the Transcendentalists. And I wonder why I felt so happy to be there.

Little did Alcott know—or perhaps she knew quite well—that she would be visited by similar sorts of pilgrim-tourists who flocked to Concord in the 1860s and who, in the words of Alcott, “roost upon Concordian fences, chirp on Concordian doorsteps, and hop over Concordian fields and hills, scratching vigorously, as if hoping to unearth a new specimen from what is popularly believed to be the hot-bed of genius.” I wonder how much today’s roosting, chirping, hopping, scratching, and hoping resemble that of the nineteenth century. I wonder how much the myth has changed since the The Scarlet Letter (1850) became THE book to study for the English AP test. I wonder when high school English teachers started crying over the Transcendentalists. And I wonder why I felt so happy to be there. So to all you college professors who teach courses on religion in America—the next time you’re covering the Transcendentalists, don’t just spend the hour situating this or that author within the larger movement of romanticism or placing this or that idea within the larger tradition of liberal Protestantism. Instead, remember your audience. Hell, remember yourself. Reflect upon how this ridiculously quotable, glaringly tiny group of American thinkers became so pervasive in American culture and so interesting or boring but nonetheless known to you and your students. Heaven knows they’ve never heard of old John Winthrop, who, by the way, you can also visit next time you’re in the Boston area at the King’s Chapel Burying Ground.

So to all you college professors who teach courses on religion in America—the next time you’re covering the Transcendentalists, don’t just spend the hour situating this or that author within the larger movement of romanticism or placing this or that idea within the larger tradition of liberal Protestantism. Instead, remember your audience. Hell, remember yourself. Reflect upon how this ridiculously quotable, glaringly tiny group of American thinkers became so pervasive in American culture and so interesting or boring but nonetheless known to you and your students. Heaven knows they’ve never heard of old John Winthrop, who, by the way, you can also visit next time you’re in the Boston area at the King’s Chapel Burying Ground.And to all you folks who plan to visit the site of Thoreau’s shed and remains, watch out for the high school cross country teams at Walden Pond and skateboarders at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. They’re courteous, but many.

For a few recent books on Transcendentalism and other related matters, see Philip Gura’s American Transcendentalism: A History (Hill and Wang 2008); John Matteson’s Eden’s Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father (W.W. Norton 2007); Dean Grodzins’ American Heretic: Theodore Parker and Transcendentalism (Univ. of North Carolina 2007); Sterling Delano’s Brook Farm: The Dark Side of Utopia (Belknap/Harvard 2004); and David Robinson’s Natural Life: Thoreau’s Worldly Transcendentalism (Cornell 2004). For a 2002 NPR report on Thoreau’s Walden, go to this link.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar